Eye For Film >> Movies >> Sandra (1965) Film Review

Sandra

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

A heady slice of Sixties Italian melodrama, Sandra is a film so furiously emotional that it might easily be perceived as comedy by a modern audience, yet it is suffused with beauty like all Visconti's work, too pleasing to the eye and too visibly a product of genius to be discounted so lightly. Though it lacks the subtlety of his best work and is very much a work of its time, suffused with Freudian angst, it is also a film whose posturing is not to be taken too seriously. Visconti, himself an aristocrat who spent his life criticising the upper classes, knew himself too well to let his protagonists' rebellion be entirely sympathetic. There are no innocents here, though many might be considered victims.

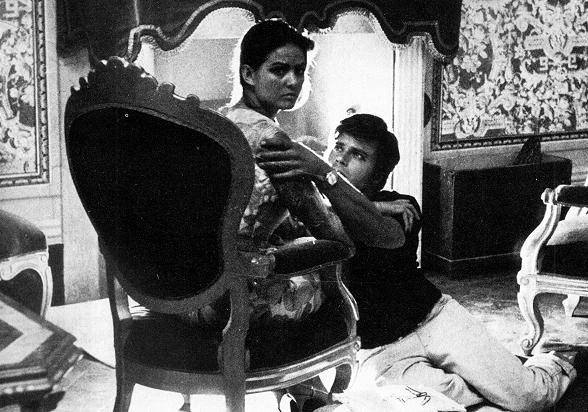

At the core of the film is Sandra herself (Claudia Cardinale, looking throughout as if she's just on the verge of punching somebody). With recently acquired husband Andrew (Michael Craig) in tow, she arrives back at her largely abandoned family mansion to prepare for a ceremony honouring her late father. In accordance with the Elektra myth underscoring the story, she believes her father was betrayed by her mother and stepfather, leading to his death at the hands of the Nazis. Ever since childhood she and her bother Gianni (Jean Sorel, to whom Luke Hamill bears a telling resemblance) have plotted revenge. But when Sandra and Gianni meet again, it's clear that something else connects them - and thus begins the unravelling of a secret so terrible that it has defined both their lives.

What that secret is won't take viewers long to guess. The power of the film comes not from its mystery but from its drama, from Cardinale's incredible screen presence and Visconti's vivid visual ideas. A myriad reflections suggest the complementary nature of Sandra and Gianni and the incompleteness of both. The director, himself rendered an outsider by his homosexuality, approaches moral issues with an ambiguity unusual in cinema of the time and never forgets the humanity of his characters. Stunning shots of the house dwarf them, presenting them as heirs to a fate much bigger than any one of them could hope to control. The sense of doomed romance found here foreshadows The Leopard and Death In Venice, and whilst it isn't one of Visconti's greatest works, it's a must-see for fans, a treat for newcomers.

Reviewed on: 23 Mar 2014